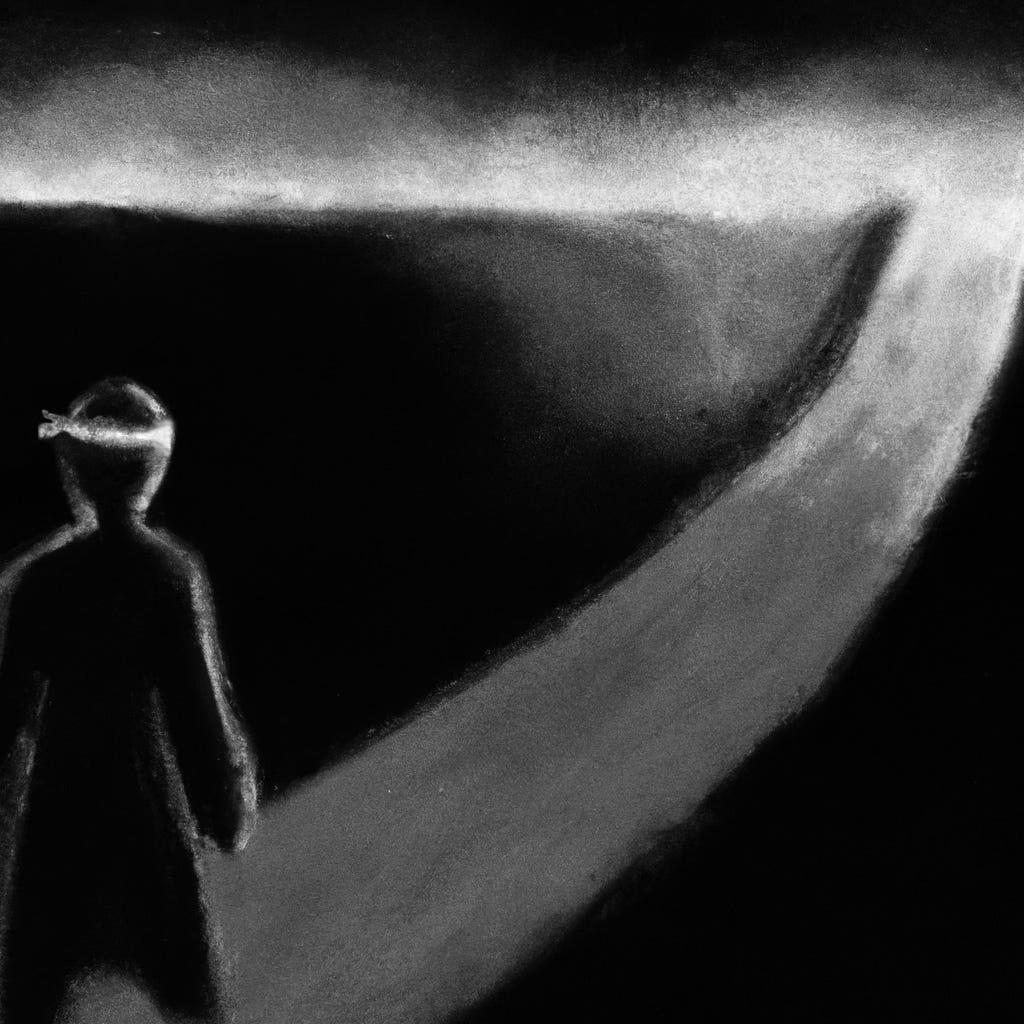

Market research without a hypothesis is a blindfolded march into the abyss.

Markets don’t reward hesitation disguised as diligence. They respond to precision anchored in conviction.

In any strategic pursuit—be it business, policy, or innovation—information is currency. But raw information is not knowledge. The mere act of gathering data does not guarantee insight. There must first be a hypothesis: a clear, testable belief about the world that the research is meant to confront. Without it, research becomes an exercise in reactive behavior, not foresight.

A market does not reveal its secrets to passive observers. It responds to provocation. A structured, directional hypothesis functions as that provocation—it sharpens perception, focuses attention, and turns observation into interrogation. The hypothesis is not a final truth. It is a calculated risk, a disciplined guess, a disciplined act of will that allows the chaos of the market to take on shape and form.

Too often, research is mistaken for safety. Stakeholders collect endless statistics, hoping to reduce uncertainty to zero before making a move. But the market cannot be conquered through caution. It can only be shaped through boldness guided by clarity. The purpose of research is not to eliminate risk, but to qualify it—to refine one’s bet, not replace it.

A clear hypothesis forces the uncomfortable. It demands commitment. It draws a line between what is and what might be. It allows for falsification. And that is the point: a rejected hypothesis is more valuable than a dozen vague confirmations. Progress emerges not from confirming the familiar but from exposing the false, confronting the flawed, and iterating forward with sharper intent.

This discipline of directional research has another effect—it separates the strategic from the superficial. Without a hypothesis, analysis becomes a retrospective justification of indecision. Every data point can be bent to confirm a bias. Every conclusion can be softened into consensus. But with a clear directional belief, there is friction, resistance, feedback. These are not obstacles. They are tools.

The march into new markets, new categories, new territories—whether commercial or intellectual—is inherently uncertain. The question is not how to remove this uncertainty, but how to wield it. A blindfolded march may feel safe, but it ends in the abyss. Directional research—anchored in a clear hypothesis—is the only way to walk forward with vision.