Due diligence often masks fear of being wrong alone.

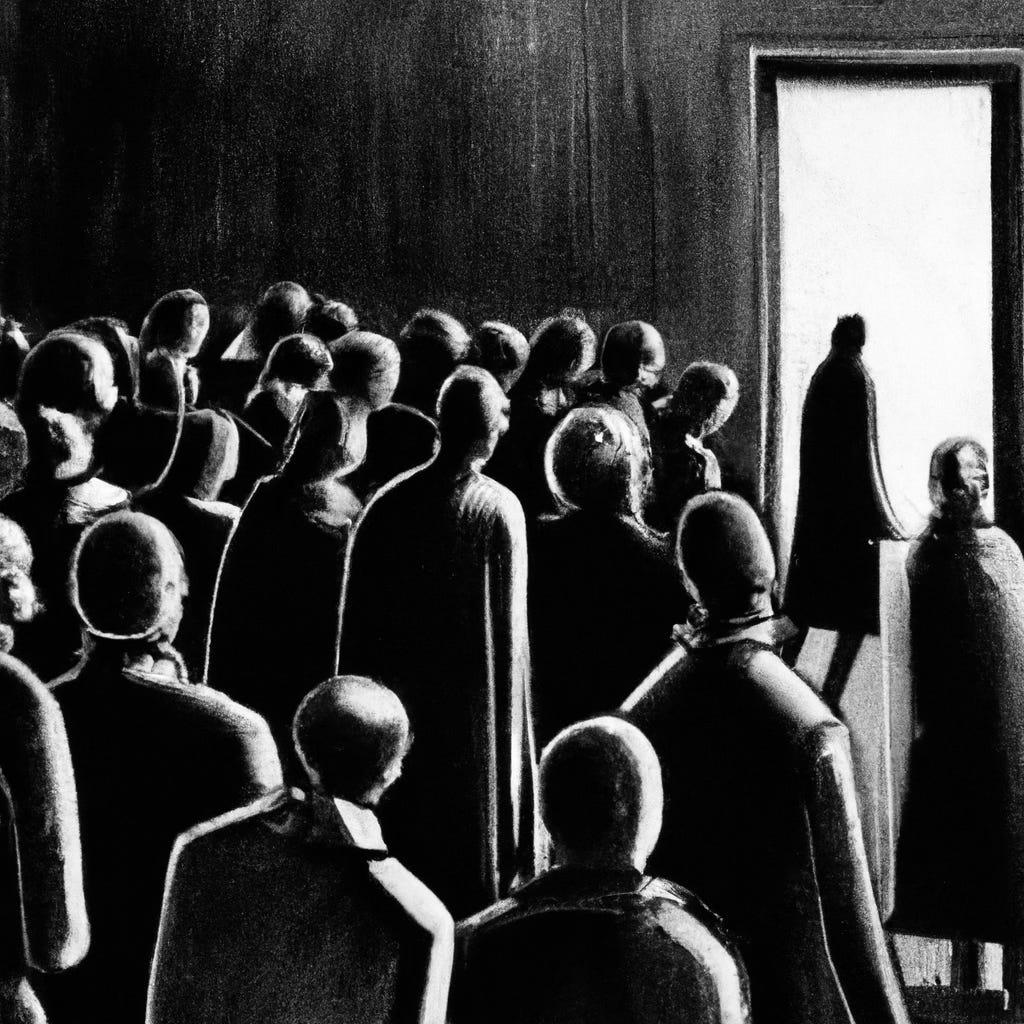

Being wrong together feels safer than being right alone. Progress fades when consensus matters more than conviction.

In modern organizations, due diligence has expanded far beyond risk management. It has become a ritual of collective reassurance, designed less to discover truth and more to distribute blame. Decisions are not strengthened by the number of approvals but diluted by them. What emerges is not clarity, but comfort: a shared narrative that ensures no single actor must bear the cost of being wrong. This mechanism rewards conformity while presenting itself as prudence, and it quietly shifts the goal from correctness to acceptability.

The highest-impact decisions rarely survive this process. They are, by nature, asymmetric, uncomfortable, and poorly supported by existing data. Breakthroughs appear irrational until they succeed, and irresponsible until they redefine the standard. Excessive diligence filters out precisely those judgments that require uncommon perception rather than statistical backing. What remains are incremental choices optimized for defensibility, not transformation. In this environment, intelligence is measured by alignment, not by insight.

There is an unspoken fear beneath the process: isolation. Being wrong is tolerable when shared; being wrong alone is existentially threatening in hierarchical systems. As a result, decision-makers outsource conviction to frameworks, committees, and benchmarks. Responsibility is fragmented until no one truly decides. Yet history demonstrates that advancement originates from individuals willing to act without permission, without guarantees, and without the shelter of consensus. Progress does not ask for validation; it imposes itself after the fact.

A different standard is required—one that treats diligence as a tool, not a shield. Analysis should sharpen judgment, not replace it. The role of expertise is to inform decisive agency, not to anesthetize it. When responsibility is reclaimed at the individual level, risk becomes directional rather than paralyzing. Errors become instructive instead of career-ending. Most importantly, decisions recover their creative force.

What ultimately separates stagnation from advancement is not access to information, but the capacity to act on incomplete certainty. Systems optimize for stability; individuals create discontinuity. When judgment is strong enough to stand without consensus, diligence regains its proper role: a servant of vision, not its substitute. This is where progress begins—not in collective agreement, but in the resolve to move first and be accountable alone.