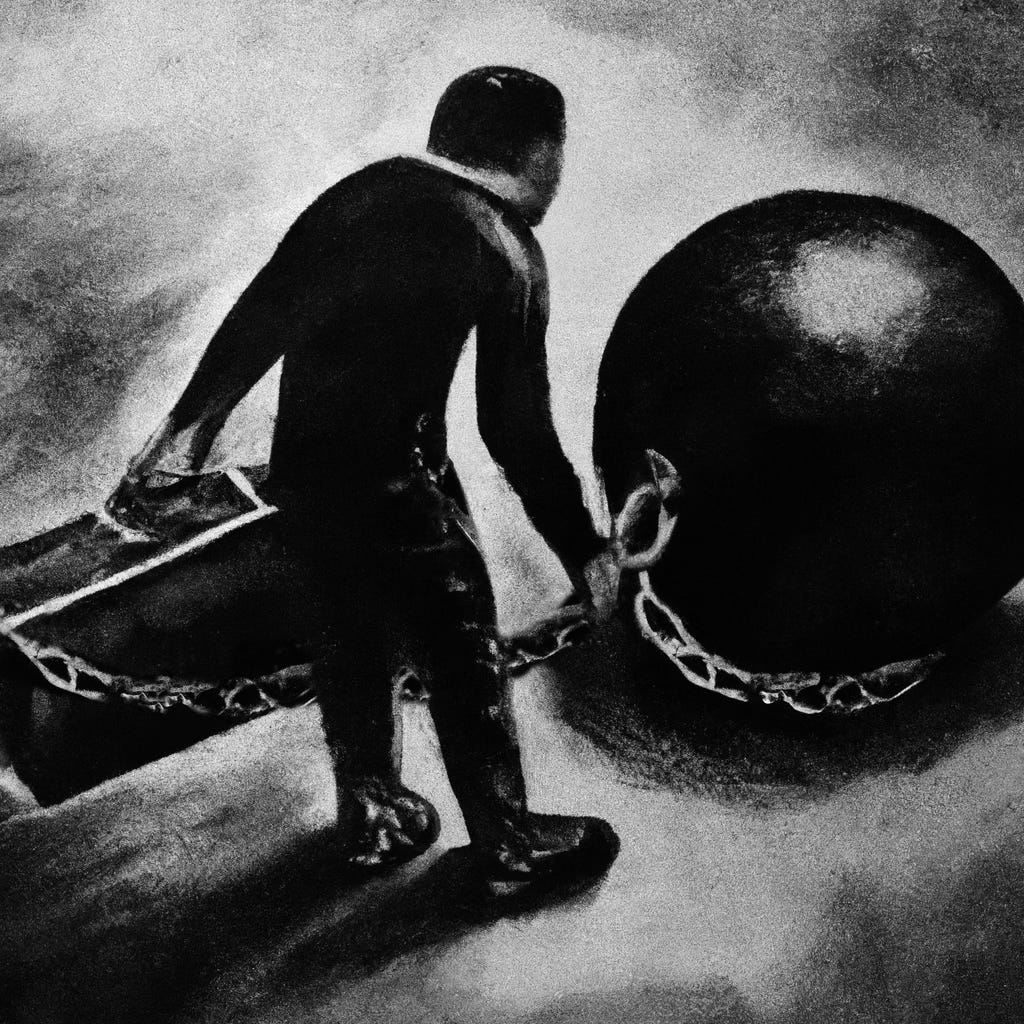

Debt is slavery disguised as opportunity.

Debt is presented as empowerment, but in reality it locks individuals and organizations into cycles of dependence. What is marketed as freedom is often a carefully designed mechanism of control.

Debt has become the most socially accepted form of bondage. It promises access, mobility, and growth, but it silently dictates decisions long after the capital has been spent. The illusion of opportunity conceals the fact that future choices are already mortgaged. In practice, those under debt are rarely building freely; they are working to fulfill obligations determined by someone else’s terms, under someone else’s timeline.

The modern system refines this trap with elegance. Instead of chains, there are contracts. Instead of masters, there are lenders dressed as partners. Instead of punishment, there are interest rates—mathematical incentives that ensure the debtor works harder, longer, and more predictably than they ever would without them. This structure is praised as progress because it is voluntary, but voluntariness under the pressure of necessity is merely a refined form of coercion.

For individuals, debt often begins with the promise of education, housing, or business capital. Each is framed as an investment in the future. Yet these investments are rarely free choices in an open field of alternatives; they are pre-selected paths defined by the system itself. The graduate is not free to explore; they are committed to paying back. The homeowner is not liberated by ownership; they are locked into decades of repayment. The entrepreneur who raises debt-backed capital often loses the ability to pivot or rethink direction, because servicing obligations becomes the first priority.

At the institutional level, debt enforces conformity. Companies that finance growth with borrowed money often find their long-term vision subordinated to short-term repayment schedules. Nations too become trapped, balancing their budgets around servicing debt rather than shaping independent strategies for their people. In all cases, the debtor must justify existence in terms of repayment rather than pure creation. Innovation becomes secondary to obligation.

The core danger lies not in debt itself, but in the psychology it produces. A person bound by obligations cannot fully act out of strength; their horizon is narrowed by fear of default. This makes them manageable, predictable, and easily aligned with systemic needs. Debt ensures compliance where rules or ideology may fail. It creates the appearance of freedom while securing obedience through invisible pressure.

Breaking free from this cycle requires a reframing of value. True opportunity is not borrowed; it is built. The capacity to create without dependence is rare precisely because it is difficult. It demands discipline, patience, and the courage to reject what is handed over easily in favor of what is constructed independently. Yet this path, though harder, cultivates strength rather than weakness.

The question is not whether debt can be useful—it can. The question is whether it can be mastered without becoming master. Most fail this test because the system is designed to blur the line between tool and shackle. The only safeguard lies in ruthless clarity: never mistaking temporary leverage for permanent freedom, never confusing systemic permission with authentic autonomy.

In the end, opportunity that arrives in the form of obligation is not true opportunity at all. It is simply another method by which the system ensures continuity, disguising necessity as choice. The real task lies in building capacity strong enough to reject dependence, so that what is created stands on its own terms, owing nothing to forces that would domesticate it.